The Star

Lifestyle

Monday May12, 2008

In days past

By WAN CHWEE SENG

Memories of an enchanted childhood

can only grow fonder with age.

Monday May12, 2008

In days past

By WAN CHWEE SENG

Memories of an enchanted childhood

can only grow fonder with age.

AS THE strains of the soulful melody waft across the silence of the sitting room, it rekindles the nostalgic memory of my childhood house. More than 50 years have lapsed since I last saw the house, but it still remains vivid in my mind.

Our house at Residential Area in Kuala Pilah, Negri Sembilan, was a typical colonial-style house that stood on concrete stilts with white wooden walls and red-tiled roof. The front opened out towards a spacious lawn.

A narrow bitumen road ran in front of the lawn and beyond it was a playing field. A narrow lane ran beside the house. The playing field, the front lawn, the lane and the space beneath the house were the playgrounds of my youth.

In the early days of my childhood, the space beneath the house was my favourite haunt. Here, my brother, sisters and I spent many hours playing in its cool shade. We would blow at the fine loose soil that carpeted the ground to expose the grey beetles hidden just below the surface.

We hunted for tiny holes in the ground. Using the long stem of a grass, we would wet one end of the stem with the tip of the tongue and carefully thread it down the narrow hole. We waited patiently for the slight movement in the stem and then yanked it out. A big, black ant, still clinging to the stem, would lie dazed and disorientated on the ground. We would examine the ant before letting it crawl back into its nest.

During the weekends, morning would often find us playing masak-masak beneath the house. My younger sisters would “cook” in pots and pans which were discarded tins and my brother and I did the “marketing”. We would pull out the wild plants and pick flowers that grew beside the drain and occasionally pinch the leaves of the vegetables that clung to the fence of our neighbour’s garden.

The lane beside the house was the meeting place of our neighbourhood teenage gang whose members were all Indians, with the exception of my brother and I.

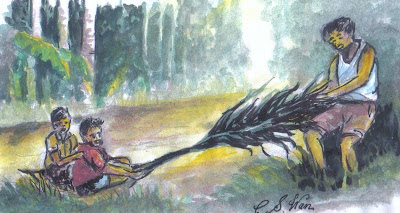

When the hockey season arrived, we would converge on the playing field armed with hockey sticks of various shapes and sizes. The sticks were home-made, specifically designed and tailored to our personal requirements.

They were mostly sourced from the bushes which fringed the residential area. Any branch which had the slightest semblance of a hockey stick would quickly fall victim to our knives. Our hockey balls were used tennis balls donated by kind members from the nearby Ulu Muar Club.A narrow bitumen road ran in front of the lawn and beyond it was a playing field. A narrow lane ran beside the house. The playing field, the front lawn, the lane and the space beneath the house were the playgrounds of my youth.

In the early days of my childhood, the space beneath the house was my favourite haunt. Here, my brother, sisters and I spent many hours playing in its cool shade. We would blow at the fine loose soil that carpeted the ground to expose the grey beetles hidden just below the surface.

We hunted for tiny holes in the ground. Using the long stem of a grass, we would wet one end of the stem with the tip of the tongue and carefully thread it down the narrow hole. We waited patiently for the slight movement in the stem and then yanked it out. A big, black ant, still clinging to the stem, would lie dazed and disorientated on the ground. We would examine the ant before letting it crawl back into its nest.

During the weekends, morning would often find us playing masak-masak beneath the house. My younger sisters would “cook” in pots and pans which were discarded tins and my brother and I did the “marketing”. We would pull out the wild plants and pick flowers that grew beside the drain and occasionally pinch the leaves of the vegetables that clung to the fence of our neighbour’s garden.

The lane beside the house was the meeting place of our neighbourhood teenage gang whose members were all Indians, with the exception of my brother and I.

When the hockey season arrived, we would converge on the playing field armed with hockey sticks of various shapes and sizes. The sticks were home-made, specifically designed and tailored to our personal requirements.

Sometimes someone would turn up without a hockey stick. With a jab of the thumb, he would be directed to the nearby teachers’ quarters. The poor boy would creep stealthily towards the bamboo hedge which surrounded the quarters. He would uproot a whole bamboo plant and return with a “hockey stick” that resembled a primitive club from the Middle Ages. The fast receding hedge bore testimony to its frequent use.

When the weather was bad or there were not enough members for outdoor activities, we would assemble under the shade of the drumsticks tree and swap empty cigarette boxes or play with our fighting spiders.

When the weather was bad or there were not enough members for outdoor activities, we would assemble under the shade of the drumsticks tree and swap empty cigarette boxes or play with our fighting spiders.

We kept the fighting spiders in match-boxes or other small containers with holes for ventilation. We hunted for them among the leafy hedges around the neighbourhood or among the bushes.

Only the male spiders which had dark green rumps were sought after because of their fighting qualities. The spiders were let to fight on the flat surface of a match-box. We watched as the spiders clawed and bit each other in a bout for supremacy. The vanquished would turn tail and flee or squirm in defeat. Both victor and loser would be returned to their respective match-boxes to be fed and readied to fight another day.

|

| A fighting spider |

My sisters would play with their dolls which were two tightly rolled pieces of cloth, shaped into a cross and secured with thread. The dolls’ dresses were fashioned from remnants of cloth. Meanwhile, my brother and I played with our toy cars made from discarded shoe-boxes. Mother knitted while Father read.

The soft sound of music from the old Grundig radio would drift across the small living room into the darkness of the lawn. Father would pause from his reading to sing and tap to the tunes of Springtime in the Rockies, Carolina Moon, Red River Valley and other hits of the 1950s. We sang or hummed along with him.

The darkness over the lawn would suddenly be punctuated with tiny flickering lights.The soft sound of music from the old Grundig radio would drift across the small living room into the darkness of the lawn. Father would pause from his reading to sing and tap to the tunes of Springtime in the Rockies, Carolina Moon, Red River Valley and other hits of the 1950s. We sang or hummed along with him.

"Fireflies!" We shouted excitedly.

We grabbed the nearest glass containers, rushed onto the lawn, and caught the fire-flies that flitted about in the darkness. In the comfort of the living room we watched them glow in the containers until the glow grew dimmer and dimmer and darkness reigned again. Then we released them into the cool night air.

“Lunch time! Daydreaming again?” A voice from the kitchen jolts me out of my reminiscences and I return to the present.

Through bleary eyes I looked around me. My grandchildren’s Barbie dolls lie scattered all over the floor. A remote control car is wedged between the door and wall. Over the whirring sound of a food processor, a DVD player is blaring: “Those were the days, Oh yes those were the days” (Those Were the Days, My Friend, sung by Mary Hopkins).

Yes, sometimes it is nice to relive the happy memories of our childhood, but we should also learn to live with the reality of the present. Having put pen to paper, we will carry on with our lives, having been assured that those memories will be with us forever.

A video on "In days past"

Related articles:

Please click below links and scroll down

Finding our way home

Gifts from a stranger

Through bleary eyes I looked around me. My grandchildren’s Barbie dolls lie scattered all over the floor. A remote control car is wedged between the door and wall. Over the whirring sound of a food processor, a DVD player is blaring: “Those were the days, Oh yes those were the days” (Those Were the Days, My Friend, sung by Mary Hopkins).

Yes, sometimes it is nice to relive the happy memories of our childhood, but we should also learn to live with the reality of the present. Having put pen to paper, we will carry on with our lives, having been assured that those memories will be with us forever.

A video on "In days past"

Related articles:

Please click below links and scroll down

Finding our way home

Gifts from a stranger