Startwo Monday 24th November 2008

BONDS THAT LAST A LIFETIME

By WAN CHWEE SENG

Memories of life in a small village, burn bright through the years.

TOOT! toot! A maid rushes out to open the front gate. Children tumble out of the car, their bodies bent double by the weight of their engorged school bags.

Toot! The maid is reminded to close the gate.

Toot! There is a long blare of the horn as the maid is given a final reminder to lock the door before the mother rushes off to send another child for piano lesson.

Things were so different in my days. Our days were carefree and life moved at a leisurely pace.

It was the mid-50s. After Father passed away, we returned to our hometown and stayed with our grandparent in the small village of Batu Berendam, Malacca. The place where we lived was a peranakan enclave where the residents spoke the Baba patois – Malay with a smattering of Hokkien.

I vividly remember the wooden house with its palm-thatched roof, hard-beaten earthen floor and a central pillar made from a whole circular tree trunk. The doors stood open from morning to dusk, and friends and neighbours moved freely in and out of the house.

In those days, we did not wake up to the musical chimes of an alarm clock. We woke up to the sound of the first cock crow. Mother would wake up at five in the morning to prepare breakfast that would sustain us until we returned from school. Our school bags were light and our pockets much lighter. Our mostly hand-down textbooks hardly changed with the years.

In the pre-dawn darkness, we would trudge along a dirt track flanked by tall lalang and towering coconut trees to wait for the school bus under the shade of a durian tree.

On dull, grey mornings when there was insufficient light, we carried torches made from coconut leaves to light our way and keep at bay the snakes that might lurk in the tall grass.

When there was a downpour we zigzagged our way along the muddy path with banana leaves held high over our heads.

It was the mid-50s. After Father passed away, we returned to our hometown and stayed with our grandparent in the small village of Batu Berendam, Malacca. The place where we lived was a peranakan enclave where the residents spoke the Baba patois – Malay with a smattering of Hokkien.

I vividly remember the wooden house with its palm-thatched roof, hard-beaten earthen floor and a central pillar made from a whole circular tree trunk. The doors stood open from morning to dusk, and friends and neighbours moved freely in and out of the house.

In those days, we did not wake up to the musical chimes of an alarm clock. We woke up to the sound of the first cock crow. Mother would wake up at five in the morning to prepare breakfast that would sustain us until we returned from school. Our school bags were light and our pockets much lighter. Our mostly hand-down textbooks hardly changed with the years.

In the pre-dawn darkness, we would trudge along a dirt track flanked by tall lalang and towering coconut trees to wait for the school bus under the shade of a durian tree.

On dull, grey mornings when there was insufficient light, we carried torches made from coconut leaves to light our way and keep at bay the snakes that might lurk in the tall grass.

When there was a downpour we zigzagged our way along the muddy path with banana leaves held high over our heads.

|

| Banana leaves for umbrellas |

Lunch was a simple meal of white rice, with a pinch of sambal belacan, a dish of home-grown vegetables and a generous topping of spicy gravy. At lunchtime, my cousins and friends from the neighbouring houses would sometimes gather under a rubber tree behind my grandparent’s house.

|

| Sharing our food |

“Cekek darah budak-budak ini! Dah petang belum mandi lagi,”( You can swallow blood with these children! It’s already evening and they haven’t taken their bath) a feminine voice grumbled to herself.

We quickly stripped to the waists, grabbed our towels and descended stealthily down the slope to the well under a starfruit tree. We did not have the luxury of body-wash with its various fragrance, toothpaste or the 2-in-1 shampoo. Each of us carried a small piece of the all-in-one soap – the hard, oblong soap which was cut to the desired length and used for bathing, laundry, dish-washing and general cleaning.

In those days there was no television or computer so we spent much of our time roaming the neighbourhood with our heads full of schemes.

We played with toy guns made from hollowed bamboo stems. The “bullets” were wild berries which we inserted into the hollow bamboo and popped out with another smaller bamboo stick.

We quickly stripped to the waists, grabbed our towels and descended stealthily down the slope to the well under a starfruit tree. We did not have the luxury of body-wash with its various fragrance, toothpaste or the 2-in-1 shampoo. Each of us carried a small piece of the all-in-one soap – the hard, oblong soap which was cut to the desired length and used for bathing, laundry, dish-washing and general cleaning.

In those days there was no television or computer so we spent much of our time roaming the neighbourhood with our heads full of schemes.

We played with toy guns made from hollowed bamboo stems. The “bullets” were wild berries which we inserted into the hollow bamboo and popped out with another smaller bamboo stick.

|

| A 'bamboo gun' and wild berries for 'bullets' |

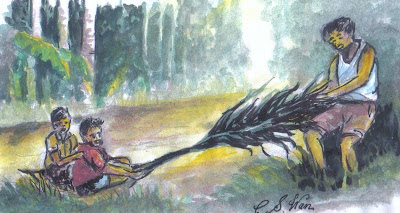

We ventured into waist-high grass to search for fallen betel nut leaves. Sitting on the broad fronds of the leaves and being pulled by our playmates, we raced each other down gentle grassy banks. Our boisterous laughter would echo in the late afternoon air as we rolled and tumbled down the slopes.

|

| Our 'car' |

Sssh! An index finger pressed firmly against his pouting lips, a cousin waved us out of the back door. Buckets in hand, we tip-toed quietly out of the house and headed for the irrigation canal that ran along the abandoned railway track. Having dammed both ends of the canal, we bailed out the water. Ankle-deep in mud, we made a grab for the carps, catfish and eels that thrashed and wriggled in its muddy shallows.

|

| Stung by a catfish |

That particular morning, we emerged unscathed from the catfish, but we were not spared from the leeches that clung stubbornly to our legs. We either let them have their fill of our blood until they dropped like soaked black beans to the ground or forcefully peeled them from our skin.

|

| Edible ferns |

“Mak,” whispered a voice. The tip of a rattan cane could be seen peeping from behind her back. We fervently hoped the abundant catch and bundles of ferns would help placate her anger.

Dusk. The babies were hurriedly bundled into the house. The older children were ushered in. We were warned not to venture out. It was not the fear of kidnappers that kept us in, but the fear of malevolent spirits which we were told would lure naughty children away from their homes.

The different ghosts the adults told us were more than we could count on our little fingers. As we peered through the half-opened windows and watched the darkness creep across the countryside, our fertile imagination took flight.

Darkness cloaked the village. The windows were shuttered. The flimsy doors were finally secured with wooden bars. Break-ins were a rarity, but chicken thefts were common.

On dark, rainy nights we would sometimes wake up at the sound of squawking and fluttering of wings. Afraid to venture into the dark night, we would just give a shout to scare away the chicken thief or civet cat.

At night we studied under the pale, flickering light of oil lamps. There was no music to keep us company nor were we distracted by the blare of television. Only the muffled, incessant chirps of crickets and the occasional belching sound of frogs from the nearby pond filled the night air.

At 10pm, the lights were dimmed. We retreated to the sparsely furnished bedroom and slept on mengkuang mats spread out on a wooden platform.

Years have passed. We all have our own houses. But on festive occasions we still return to our ancestral home in Batu Berendam to rekindle old ties and strengthen family bonds.

The wooden house where we grew up is now a brick building. The many fruit trees which provided us with succulent fruits and the rubber tree where we used to gather for lunch have all been uprooted. In their place stand rows of stereotype brick buildings.

Pale lights still flicker through tinted windows, but they are lights from the television picture tubes. The lights of oil lamps have long been extinguished and the oil lamps are things of the past.

Like the oil lamps, the village of my youth is just a distant memory.

Related articles:

Please click below links

In Nature's Embrace

Memories of kampung shops

The different ghosts the adults told us were more than we could count on our little fingers. As we peered through the half-opened windows and watched the darkness creep across the countryside, our fertile imagination took flight.

Darkness cloaked the village. The windows were shuttered. The flimsy doors were finally secured with wooden bars. Break-ins were a rarity, but chicken thefts were common.

On dark, rainy nights we would sometimes wake up at the sound of squawking and fluttering of wings. Afraid to venture into the dark night, we would just give a shout to scare away the chicken thief or civet cat.

At night we studied under the pale, flickering light of oil lamps. There was no music to keep us company nor were we distracted by the blare of television. Only the muffled, incessant chirps of crickets and the occasional belching sound of frogs from the nearby pond filled the night air.

At 10pm, the lights were dimmed. We retreated to the sparsely furnished bedroom and slept on mengkuang mats spread out on a wooden platform.

Years have passed. We all have our own houses. But on festive occasions we still return to our ancestral home in Batu Berendam to rekindle old ties and strengthen family bonds.

The wooden house where we grew up is now a brick building. The many fruit trees which provided us with succulent fruits and the rubber tree where we used to gather for lunch have all been uprooted. In their place stand rows of stereotype brick buildings.

Pale lights still flicker through tinted windows, but they are lights from the television picture tubes. The lights of oil lamps have long been extinguished and the oil lamps are things of the past.

Like the oil lamps, the village of my youth is just a distant memory.

Related articles:

Please click below links

In Nature's Embrace

Memories of kampung shops

The article helps to rekindle memories of my own

ReplyDeletechildhood days in Penang. Though it was not that colourful, I remember the early years when I used to walk along the dark and often deserted alley-way to my school.