paddy field

By Wan Chwee Seng

It stood, solitary, isolated and different.

While the others in the neighbourhood stood in clusters with wooden stilts and palm-thatched roofs, the wooden bungalow was raised on concrete stilts and sported an asbestos roof.

A tangle of greenery with towering trees, their moss-wrapped branches festooned with vines, enclosed the back of the house. To the left, close to the house, was a well ringed with a low brick wall and beyond it, across a ground thickly carpeted with dried foliage, was an outhouse. With flimsy plank walls and a zinc roof, the outhouse stood solitary under a gnarled rubber tree with bare branches

|

| The wooden bungalow house |

A tangle of greenery with towering trees, their moss-wrapped branches festooned with vines, enclosed the back of the house. To the left, close to the house, was a well ringed with a low brick wall and beyond it, across a ground thickly carpeted with dried foliage, was an outhouse. With flimsy plank walls and a zinc roof, the outhouse stood solitary under a gnarled rubber tree with bare branches

The front of the house overlooked a paddy field: a patchwork of verdant vegetation during the planting season and a sea of billowy gold at harvest time. An irrigation canal, a rivulet of gurgling water, flowed along the edge of the field and one corner of the field was framed by a clump of bamboo with willowy plumes that swayed gently in the breeze.

|

| The lush paddy field |

"Oh, What a lovely view!”, the few visitors who made brief

stopover exclaimed ecstatically as they gazed at the picturesque vista.

However, the residents of the house, teachers from the nearby Rantau Panjang English School and others from the Malay school in Gual Periok, knew that appearance can often be deceptive.

Although the house was fairly big, it was sparsely furnished: the hall was bare while each of the two rooms was equipped with simple wooden beds and a small writing table. It was the early 1960s and Rantau Panjang was still without electricity and most of the houses had no running water.

During the day, to while away the hours, we played scrabble, outdoor games, or got together for a sing- along session.

|

| A Sing-Along session. From Lto R. The writer, Lim, Hassan and Kwok |

We even had our own staff hockey and soccer teams and we used to participate in friendly games with the other schools in the state. I remember there was a year when we won the teachers ’six-a-side soccer competition organised by the state’s NUTP. I was told that when our team representative went up the stage to collect the prizes there was a big applause accompanied with shouts of ‘steady Sungai Golok’.

As soon as the last shadow melted into dusk, the oil lamps were readied for the night. We read and did our work in the pale, flickering glow of the oil lamps. Without a radio in the house to entertain us, we sat in the tranquility of the night and listened to nature’s orchestrated music: the incessant chirps of the myriad insects and the deep belching of frogs from the nearby paddy fields.

At the first light of dawn the relaying calls of the roosters stirred us from our slumber. With eyes still heavy with sleep, we made our way to the nearby well.

I remember on the first day we moved into the house, Lim and Kwok, both city boys, went to the well for a bath. As there were only two pails available at the well I let them have the pleasure of testing the water, while I waited upstairs. From my room I could hear a dull thud as a pail hit the water and this was followed by more thuds, but there was no sound of cascading water. Curious, I peered through an open window. Sweat was streaming from both their faces, but their bodies were still dry. I watched and smiled as I saw them throwing the pails forcefully into the water. The pails landed with a loud thud, but when they drew up the pails all they had to show for their effort was a tiny puddle of water at the bottom of the pails. I decided it was time to show them the ropes.

“That’s not the right way to draw water,” I called out, as I approached them.

Taking a pail from one of them, I said,

“This is how you draw water.”

“First you lower the pail slowly with the rope until it touches the surface of the water. Then give the rope a gentle tug, to allow the rim of the pail to break the surface of the water and let the water trickle into the pail. When the pail is filled to the brim, slowly draw it up.”

After a few failed attempts, they managed to master the technique. I left them to enjoy their bath. From my room I could hear the sounds of cascading water and boisterous laughter and I knew both of them were having a splashing time.

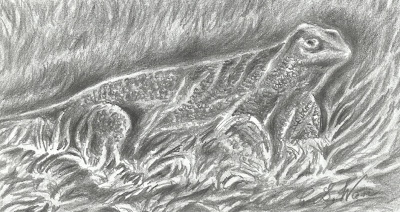

Sometimes our bath would be interrupted by the crackle of twigs and dried foliage, as monitor lizards, some the size of a small crocodile, emerged from the dense undergrowth and headed towards the house. We tried to scare them off, but they were oblivious to our shouts and would waddle languidly across the ground, eyeing us menacingly through heavy-lidded eyes.

|

| A monitor lizard eyeing us through heavy-lidded eyes |

However, the moment we bent to pick up a stone or even before one of our colleagues could string his bow to test his archery skill they could sense the imminent danger and would scurry and vanish into the dense undergrowth.

There were nights when our stomachs would groan and rumble, not because of hunger but due to a more urgent call.

I remember vividly one late night when I began to pace the floor while I thought about the isolated and deserted outhouse that was sited about fifty metres from the house. At the unearthly hour the half-remembered lesson on Shakespeare of my schooldays suddenly came to mind:

“To go, or not to go, that’s the question.”

Then as goose pimples began to ripple up my arms and beads of cold perspiration appeared on my forehead I knew ‘you got to go when you got to go’.

Taking a small oil lamp from the table I stepped into the darkness outside. Only the crunch of leaves underfoot could be heard, as I trod gingerly towards the outhouse. A faint rustle among the shadowed shrubs made me pause momentarily, as I thought about the monitor lizards lurking in the deep shadow. Were they lurking in the shadows to exact their revenge?

I heaved a sigh of relief when I reached the safety of the outhouse. However, enclosed within the constricted space, the oil lamp began to throw long ghostly shadows on the wooden walls while outside the night wind began to knife through the chinks of the flimsy walls. Overhead, as finger-like twigs clawed at the roof, it conjured image of a white figure perching on the low branch.

|

| The outhouse under a gnarled rubber tree |

To the right side of the house was a vacant patch of land with a narrow dirt track that led to the town’s unpaved road. During the dry season, the ground was a grey mass interlaced with cracks that made it appear like a faulty jigsaw puzzle. However, during the monsoon period the ground would be transformed into a slippery morass. As our slippered feet squashed the squishy ground, we kept a wary eye on the ankle-high grass as we knew leeches were waiting to suck our blood..

Attracted by the smell of warm human blood, the tiny, black creatures would converge from every directions, stretching and arching their elastic bodies with amazing speed, as they advanced towards us. It was not unusual to find them clinging to our legs and arms long before we reached the house. We were told that peeling them forcefully would leave a lingering itchiness, so we let them have their fill. Engorged with blood they looked like soaked black beans and fully satiated would drop quietly to the ground.

Today, years on, as I rest in the comfort of a bedroom with an attached bathroom, I let my mind drifts to that distant days when we stayed at the house by the paddy field. Although, we had to face deprivations and tribulations then, the experiences have taught me to appreciate and be grateful for the little things we tend to take for granted.

.

Nice...I like the nocturnal visit to the outhouse the best!

ReplyDelete